Archive of the Month

Letters from the Western Front

Archive of the Month – December 2012

To access the Letters slideshow,

please click here

The parish of Dundela, Belfast

Established in 1876, Dundela was the first ‘modern’ parish to be created in the growing suburbs of east Belfast and as such, is clear evidence of Belfast’s rapid expansion from the latter half of the 19th century onwards. Dedicated to St Mark and situated in a prominent position on the crest of Bunker’s Hill, on the main Holywood Road going towards the Bangor Road, the parish church’s distinctive sandstone belltower was once visible from all over Belfast, and whilst now subsumed into greater Belfast today, continues to be a conspicuous landmark. The church was designed by William Butterfield, the English Tractarian architect, and consecrated on 22 August 1878 when the district of Dundela was granted full parochial status.

At the turn of the 20th century, the social profile of Dundela parish was varied and interesting – representative of Belfast’s diverse and growing population. Carved originally from the wealthy parish of Holywood where many of Belfast’s most prominent families had their houses and villas, Dundela too had its share of leading merchant and manufacturing families among its parishioners, and they, as well as a growing number of professional lawyers and doctors, played a leading role in the development of their church from 1876. The notable Christian writer and academic Clive Staples ‘Jack’ Lewis was a famous son of the parish. He had been baptised in St Mark’s church in 1899 by his grandfather, the Reverend Thomas Hamilton, then rector of the parish, and his family was indicative of the rising middle class’s presence in Dundela.

In addition to the rising middle class and wealthy elite however, the social makeup of Dundela was further enriched by the families of numerous working men earning the weekly wage in Belfast’s factories, mills and shipyards, and their families, many of whom resided in the village of Strandtown, nearer to Knockbreda parish from which the parish of Dundela had also been originally carved. Indeed, according to the centenary history of the parish written by JC Beckett, Professor of History at Queen’s University Belfast in 19 78, it was mainly out of concern for the spiritual needs and religious teaching of these families that the idea of providing a new church had originally ‘taken its rise’. By 1914, on the eve of the First World War, Dundela parish consisted of no fewer than 450 families, many of them from the village of Strandtown.

Irrespective of social class, the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in August 1914 united parish men and their families in the cause to defeat a common enemy. In spite of the difficulties and worries presented by the absence of very large numbers of young men who had signed up for army service leaving their families behind, coupled with the absence from church activities of many other male parishioners, who, whilst unfit for active service, made their own wartime contribution with overtime in the shipyard and other industries, community spirit was strengthened as the war effort continued. The distractions of the times saw the parish’s Men’s Society cease for the duration of the war and much diminished in numbers thereafter, while a Bible study class hitherto organised for male parishioners also folded. While Sunday attendance for worship increased, it was the women left behind, their children and the elderly, who swelled the numbers while those seats occupied by fathers, brothers and sons lay empty.

In October 1914, the parish magazine (still in the custody of St Mark’s parish) recorded an initiative aimed at involving the women parishioners in the war effort. Entitled ‘Knitting for Soldiers’, it represented the parish’s contribution to a larger scheme of ‘doing something for the comfort of our men at the front’, which involved ‘working parties for the soldiers…held all over the British Isles’. Dundela parishioners were advised that ‘the women in this parish are not behind in this’, but more were encouraged to participate:

‘A working party, to knit socks for the soldiers, was started at the beginning of the month, and 96 pairs of socks is the result. Wool is given out free to women who will come and work with it; costs nothing and a little of their labour will bring comfort to many. The members of the Mother’s Union begin their winter’s work on Tuesday, 6 October. They meet in the schoolhouse, every Tuesday at 3–30, and will carry on this good work of knitting for the soldiers. There are many women in this parish who do not attend these meetings, and could well afford to spend the hour to attend. All who come will be made welcome at these mother’s meetings which help considerably to strengthen and deepen the spiritual life, and through them help and cheer the lives of others.’

In December 1915, the parish magazine reported that the local Girls Friendly Society was making bandages as well as knitting mufflers, socks and mittens which were much appreciated by the soldier parishioners, while a month later, thanks were received from France for an air–pillow. As the war dragged on with its increasing list of casualties, support for the men at the Front grew stronger and in 1917, the Sunday school children showed their concern by going without their customary annual prizes so that the money might be used to buy gifts for prisoners of war and their families.

Much of this support was galvanised by Dundela’s new and energetic young rector, the Reverend Arthur Barton, then in his early thirties, who had been appointed to Dundela just four months before the outbreak of hostilities and who would continue in that position for several years after the war until 1925. Barton was serving his first incumbency as rector of a parish, having previously been curate of St George’s, Dublin (1904–1905), curate–in–charge of Howth in county Dublin (1905–1912), and briefly between 1912 and 1914, as head of the Trinity College Mission in Belfast, the focus of which was to provide outreach to the working class districts of Crumlin and the Shankill, comprising about 4,000 people. Following his 11–year stint in Dundela, Barton went on to have a distinguished clerical career as rector of Bangor (1925–1930), also serving as treasurer, precentor and eventually archdeacon of Down (1927–1930), before his first episcopal appointment as Bishop of Kilmore (1930–1939), and finally as Archbishop of Dublin, from 1939 until his retirement in 1956.

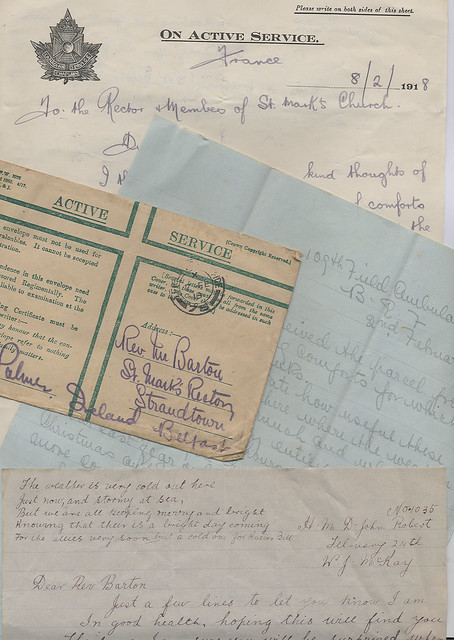

In Dundela during the Great War, Barton cut a dashing figure as he cycled around the parish, visiting and supporting families missing their loved ones and trying to encourage a wider spirit of community among those left behind. A file of his personal papers that survives from his time as rector reveals the activities that focused his particular attention: the adult and junior choirs; the Church Lads’ Brigade; the Sunday School including an annual Sunday School excursion for children and their families, and a parcel scheme of comforts sent to soldiers from the parish fighting at the Front in late 1917, revealed by the content of letters of thanks sent back to him from ten of those soldiers who had received them at the Front. Each letter reveals that the men deeply appreciated receipt of their comfort parcels and the thoughts of people at home. Their letters of thanks clearly meant a great deal to Barton because they described what they were going through, and he felt them important enough to keep together in an envelope marked simply ‘Soldiers’ Presents’.

Letters from the Front

It is remarkable that the letters have survived. Their provenance is somewhat unusual because they actually turned up in the basement of Kilmore See House, just outside Cavan town, in the context of a much larger volume of other diocesan papers. It was in this house that Barton, like other bishops of Kilmore, had resided between 1930 and 1939. He obviously took the papers with him from Belfast but for whatever reason, they did not accompany him to Dublin after his stay in Cavan and remained buried in a cupboard in Kilmore See House until the archival contents of the house were transferred in their entirety to the RCB Library in Dublin in 2007.

The Kilmore collection, comprising many wide–ranging diocesan papers for the period 1838–2003 has now been catalogued is available online at this link:

In March 1918, the parish magazine recorded: ‘several letters have been received from parishioners in France, thanking the congregation for the New Year presents and saying how useful they were in the winter weather’. A table with the details of the letter writers, including the names of each soldier, regiment / affiliation in some cases, location if given, and the date of each letter is provided at this link. For seven of the ten individuals, using the parish registers of baptism, marriage and burial still in the custody of the parish, it has further been possible to ascertain the age, the profile of the household to which they belonged, and in some cases, their position in family and full name, by cross–checking the names with the 1911 Census of Ireland, now available online at this link: www.census.nationalarchives.ie/search, and additionally for a few of them, their marital status and address from entries in the parish registers in St Mark’s church.

Taken together, the letters provide poignant descriptions of the realities of that conflict and its impact on the personal lives of families in this particular Belfast parish. Notably all ten letters were written between the end of January and late February 1918, and relate to parcels sent before Christmas when we know from parish records, fundraising was going on to raise money for Christmas gifts and women members of the Mother’s Union and Girls’ Friendly Society were devoting much time to knitting comforts for the troops.

For example, the letter of WJ Sterrett of the British Expeditionary Force written in February 1918, and makes reference to his receipt of ‘parcel safe’ on the night previous to ‘coming out of the trenches’. He had been unable to answer previously ‘owing to the scarcity of paper’ but reported himself ‘in the best of health at the present time after going over the top at the Cambrai advance’. The attack at Cambrai in northern France had been launched at dawn on the morning of 20 November 1917 and continued until early December. It heralded the first time that tanks were used in combat in significant numbers and resulted in the deaths of over 95,000 men. Sterrett survived and having returned safely from the battle, found some writing paper and a pencil to send belated thanks to the parish back home on 5 February 1918. From the parish register we learn that Sterrett was 33 years old and had been married in St Mark’s church by the Reverend Arthur Barton just three years before in June 1915 – either before he was called up or during leave from his unit.

Most of the letters are brief and to the point, such as that of G Cleary’s written on 29 January 1918, which is ‘just a line to let you know I received your parcel for which I thank you very much’, adding an apology for ‘not having writing [sic] to you sooner which I ought to have done’. However, a couple of them provide more detail, such as the letter of RV Palmer written on 8 February on the headed paper of the Canadian Service Chaplain (possibly emphasising the scarcity of paper) describing himself as ‘an old St Mark’s boy’ and providing information about the content of his parcel. From evidence in the 1911 Census, we know that he was Richard Vincent Palmer aged 24, the son of a grocer, and youngest of 11 children, from Belmont Road. From the parish registers we further learn that Palmer’s father had previously served as both sexton and verger to the church during the 1880s and 1890s, when the older siblings were born. Palmer thanked the rector and members of St Mark’s church:

‘for [their] kind thoughts of me and also for the very useful box of comforts you sent. The box contained just the things that are needed I think most by the men in the trenches. Socks are in great demand when the weather is bad and mud is everywhere, and the mitts and headgear are desirable, if not essential, when the weather is cold’.

He added that as they had experienced ‘both kinds of weather on our last trip in the line… [one] can imagine how thankful I was that your parcel had arrived the day before the battalion went into the trenches’. Alluding to unbearable conditions, Palmer concluded his letter by ‘trusting that before long we may see the end of this awful conflict’.His brother Ernest P Palmer (whom the 1911 Census confirms was three years older than Richard) was serving with the 109th Field Ambulance, and in writing his letter of thanks expressed similar hopes on 2 February 1918:

‘We can only “carry on” hoping that this will be our last year out here, and that next Christmas and new year will be spent in the more congenial atmosphere of our own homes’.

RA Brewis reminisced about ‘the many happy hours I had in the choir, and hope that (God willing) I shall one day return there, and renew old acquaintances’. Census information indicates he was Robert, a cabinet maker, while the parish register confirms that in 1913, Robert Algernon Brewis, cabinet maker, aged 23, married Caroline Moore, a stitcher, aged 21, and lived at 7 Clara Crescent. A year later on 14 June 1914, the couple’s first child, a daughter, was baptised by the newly–appointed rector Arthur Barton, and was in fact the first child he baptised in Dundela.

Another poignant letter came from CSM William Millikin of the British Expeditionary Force in France, written on 12 February 1918, whose concern for his family at home was clearly assuaged by the safe knowledge that Barton as rector paid them regular pastoral visits. As well as thanking Barton and the parishioners of St Mark’s for their gifts, he specifically acknowledges the former ‘for your own kindness to my wife and children as the letter I get from home from my wife says that you are very attentive…’.

Further evidence of Barton’s pastoral care comes from the letter of Private D.[aniel] Commerford, who signed himself ‘one of your parishioners’, in which he regrets that he missed seeing his rector before leaving for the Front, referring to Barton’s ‘visit to my house’.

Commerford explained that he had to leave ‘a day earlier than I thought I would have too [sic]’, and so did not get to say goodbye. Originally from Oxford, the 1911 Census reveals he was older than the other letter writers, aged 38 in 1918 and the father of three children between the ages of 11 and 16.

Rob. W Hanna of the British Expeditionary Force, is pleased to tell Barton that he has heard from his brother ‘Mush’ who has arrived safely in India. He alone among the letter writers seems to have known Barton more personally than the others as evidenced by his reference to rugby, trusting that Barton is keeping well and ‘still able to indulge in the odd game of rugger at Campbell

[Campbell College,

Belfast,

located within the parish boundaries]’. Less is revealed by the content of J McKernon’s letter, written from ‘somewhere’ on 26 January 1918 – his first opportunity to write and acknowledge the parcel of comforts – in which he refers to the weather as ‘very cold’.

The harsh prevailing conditions and his loneliness are clearly inferred from the concluding sentence: ‘it helps to lift one’s heart a bit when [we] get something from their friends at home. I have nothing more to say just now so I’ll close again thanking you for your kindness’.

The final letter in the collection seems more upbeat and in anticipation of victory for the Allies, as it opens with a poem:

‘The weather is very cold out here

Just now, and stormy at sea

But we are keeping merry and bright

Knowing that there is a bright day coming

For the Allies very soon, but a cold one for Kaiser Bill.’

Written by the only naval rating among the soldiers who returned thanks to the Reverend Barton, it was sent by Seaman WJ McKay on 24 February 1918, aboard His Majesty’s Dredger the John Robert, via the submarine HMS Osiris 11 and the GPO in London. McKay appears to have belonged to a club organised by Barton in his capacity as head of the Trinity College Mission prior to his move to Dundela, as he refers with respect and affection to ‘the good nights that we all spent there, with your kindness and zeal, for to keep the boys from other temptations’. It appears that McKay has been in contact with other ‘boys’ who belonged to Barton’s club, as he further reports that he has ‘had a few letters from other ones that is serving else where, and they all like to mention about the Trinity College and you’. He goes on to talk about the darts and other fond memories they had ‘up in the Rev Barton club’, drawing a sad parallel with the darts of war out at sea:

‘Boys out here that had been up in the college when we had the club up, [were] sayin how would you like to be tonight at the darts. I am sure there are a good few of the boys that would like to be going up to the club to night, for they are using the darts now that does damage when they strike, and help to make the Kaiser cry enough’.

McKay remains confident of winning the war and concludes that it will not be long until ‘the boys will come marching home with victory once more to there [sic] loved ones and friends whom they are longing for to see and renew the good times we had in the days gone bye [sic]’.

Happily, McKay and the nine other letter writers appear to have survived the Great War, in spite of the fact that 1918, the year when they wrote, was the most costly of the four years in terms of British and Irish casualties. A total of 31 parish men who died during the Great War is recorded on the 1914–1918 memorial in St Mark’s parish church, but none of the letter writers were among them. Further research conducted by the Somme Heritage Centre in Belfast http://www.irishsoldier.org confirmed that none of the ten letter writers died as a result of the conflict.

To view the ten letters from the Western Front click here or the slideshow below.

The assistance of the former rector of Dundela,

the Rt. Revd John McDowell, and the parish historian, Tony Wilson, in the research for this item is acknowledged. A fuller account of the Dundela Letters from the Western Front by Susan Hood was published in Irish Archives vol. 16 (2009).

www.dundela.down.anglican.org

Updates:

This story was featured on BBC radio (on the Good Morning Ulster show)

and television Newsline bulletins and a follow up link is available on

the BBC website at this link:

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk–northern–ireland–20818500

The December Archive of the Month content is also featured by the World War 1 Ireland Project initiated by Goldsmiths Collect, University of London and Exeter University, who have added links to their online project:research and community projects on the era of the First World War and its memory in relation to the island of Ireland.

http://irelandww1.org/News.php

www.irelandww1.org/Resources.php

For further information please contact:

Dr Susan Hood

RCB Library

Braemor Park

Churchtown

Dublin 14

Tel: 01–4923979

Fax: 01–4924770

E–mail: susan.hood@rcbcoi.org