Archive of the Month

St Brigid: A Powerful Focus of Unity

By Ella Squire, Assistant Archivist, RCB Library

St Brigid is rooted in Irish culture most evident in the way her name is preserved throughout Ireland; “wherever the Irish people are, church, schools and convents bear her name” (Sherlock, 1896). The most ubiquitous being the 36 townlands named Kilbride. Since the medieval period, Brigid has been an incredibly popular patron saint of churches and other religious houses. Currently, she is patron of 113 Roman Catholic churches and 14 Church of Ireland churches throughout the island (Kissane, 2017). Arguably, the most famous being her own: St Brigid’s Cathedral in Co. Kildare.

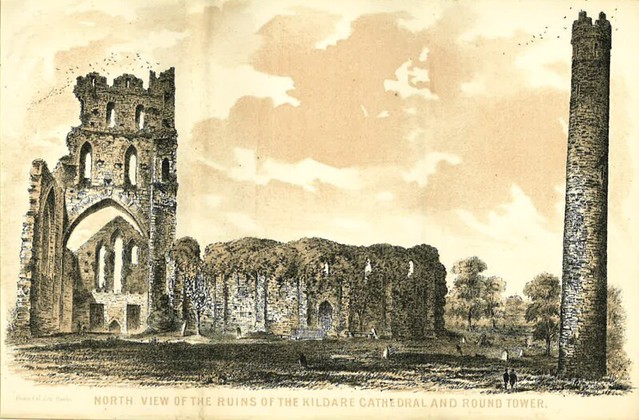

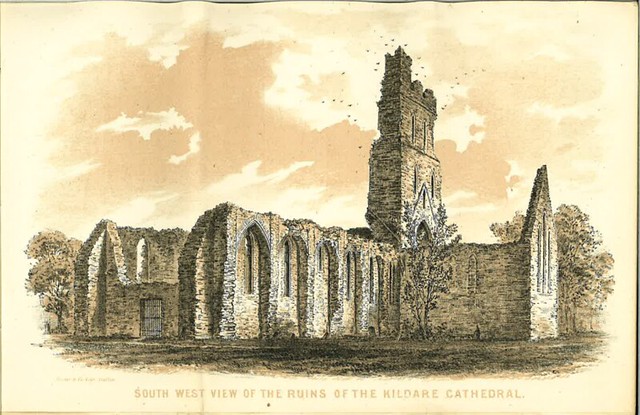

In 480, being besought by the people of Leinster to return to them, she fixed upon Drum Criadh. There, under a great oak tree, which she loved, she built her cell. Hence came the name Cill–Dara, or Kildare, the cell of the oak (Sherlock, 1896). However, a combination of raids, fires, poverty, and disestablishment over the centuries meant that by 1870, all that were left was ruins. The choir was the only part still roofed and used for service, although its “architectural character [was] of the poorest description” (RCB, C14/2.11) The west end of the nave and north transept were both destroyed. The central tower was a “mere wreck”, with only the south side still stood intact (RCB, C14/2.11). This was the state of the cathedral for over 200 years.

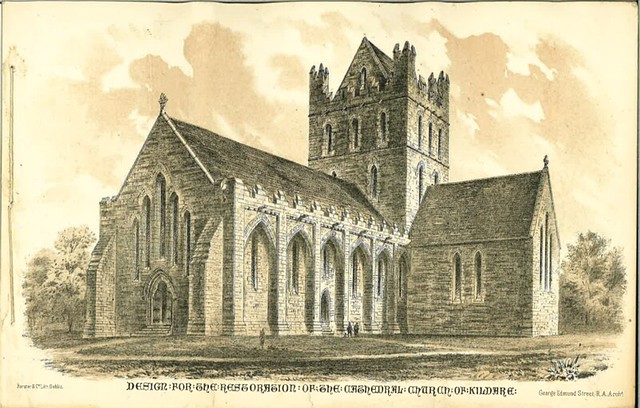

That was until one day 1871, Dr Samuel Chaplin, who lived in Kildare, looked at the ruin and expressed his hope that St Brigid’s be rebuilt. His seven–year–old son, Samuel Richard promptly offered to begin a restoration fund with a bullock he owned, valued at £5. It was this gift that encouraged the great generosity of many others (Paterson, 1982). The child’s generosity is reminiscent of a young Brigid who; “gave away freely to the poor and guests [her mother’s] milk and butter” (Freeman, 2024). A restoration committee was formed, representative of the whole diocese and county. One of the most eminent architects of the day, George Edmund Street, responsible previously for restoring Christ Church Cathedral, was consulted. Roughly £12,000 had to be raised – a massive sum for those days (Paterson, 1982). This did not dissuade the parishioners, however, as they understood the significance of the cathedral; “upon us has fallen the task… of remedying the neglect of 200 years, and preserving, while it is still possible, one of the few existing monuments of our connection with the past” (RCB, C14/2.11)

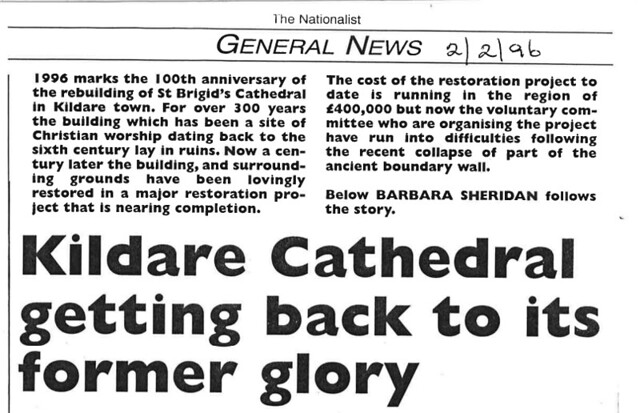

Once restored, the cathedral continued to build a sense of community, as seen in the 1996 centenary restoration, when the 100th anniversary of the cathedral’s restoration was celebrated. It also marked the completion of a major restoration project of the building’s interior and surrounding grounds, costing £400,000. As stated by Barbara Sheridan of The Nationalist (1996) this project represented “the essence of the strong community spirit as evidenced by the ecumenical support for the restoration project.”

In 1988, when St Brigid’s was, once again, in desperate need of restoration, the Roman Catholic Bishop, Dr Lawrence Ryan, responded to the invitation of Dean John Paterson by agreeing to be a patron of the project and was “one of the first to give a generous donation on behalf of the people of his diocese” (RCB, C14/2.14) The Roman Catholic people, businesses, and individuals as well as parish clergy, the Carmelites and Brigidines, all responded with equal generosity (RCB, C14/2.14). This ecumenism and community are forever symbolised in the cathedral with the erection of eight gargoyles commemorating people involved in the restoration project. This included Bishop Walton Empey, Bishop Laurence Ryan, Dean Byrne and Dean Paterson, former deans of St Brigid, Bill Hanley Tadhg Hayden, Kenneth Dunne, and Sean Lacey, all well–known Kildare people (Sheridan, 1996). “The people of Kildare town and surroundings have provided a monument to living ecumenism in the way they responded to the restoration appeal for St Brigid’s Cathedral” (RCB, C14/2.14).

This kind of spirit is reminiscent of St Brigid herself. Her power is often expressed in helping miracles, “humble affairs for people of low rank” such as healing, feeding the hungry, and rescuing the weak from violence (Charles–Edwards, 2004). Brigid never allowed the poor to go away from her empty–handed (Freeman, 2024). She was incredibly generous and focused on helping those around her, regardless of who they were. In a letter sent to the president’s office, the then Dean, the Very Revd R.K. Townley, captures the symbolism of St Brigid’s Cathedral and its ecumenical outreach; “the Cathedral is rooted in our spiritual past but stands as a challenge to a modern Ireland in danger of forgetting its spiritual and moral heritage. The community of Kildare finds a powerful focus of unity in St Brigid’s Cathedral. In a real sense St. Brigid’s belongs to all of us, and this has been expressed in the trans denominational support of the present restoration.” I believe the same argument can be made for St Brigid herself.

Happy St Brigid’s Day.

Works Cited:

Charles–Edwards, Thomas. “Early Irish Saints’ Cults and their Constituencies.” Éirú 54, (2004): 84–85, 88–89.

Freeman, Philip. Two Lives of Saint Brigid. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2024.

Kissane, Noel. Saint Brigid of Kildare: Life, Legend, and Cult. Dublin: Open Air, 2017

Paterson, John. Kildare: The Cathedral Church of Saint Brigid. Kildare, 1982

Records of St Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare. RCB Archives, Representative Church Body Library, Dublin.

Sherlock, William. Some Account of St Brigid and of the See of Kildare with its Bishops and of the Cathedral, Now Restored. Dublin: Hodges Figgis, 1896.

Sheridan, Babara. “Kildare Cathedral getting back to its former glory.” The Nationalist, 2nd February 1996.

Figures

1. Stained glass from St Etheldreda’s Church, London by Joseph Nuttgens photographed by Lawrence OP, 2008

2. Illustration of north view of ruins by George Edmund Street and published by Forster & Co., Dublin, 1871 (RCB, C14/2.11)

3. Illustration of southwest view of ruins by George Edmund Street and published by Forster & Co., Dublin, 1871 (RCB, C14/2.11)

4. Design for restoration of cathedral by George Edmund Street and published by Forster & Co., Dublin, 1871 (RCB, C14/2.11)

5. Picture of article by Barbara Sheridan of The Nationalist, 1996 (RCB, C14/2.14)

6&7. Two of the gargoyles from the cathedral, most likely Bishop Laurence Ryan and Bishop Walton Empey, photographed by The Standing Stone, https://www.thestandingstone.ie/2014/05/kildare-cathedral-high-cross-and-round.html

8. Stained glass from St Mary of the Rosary, Cong, Co. Mayo of St Brigid photographed by Andreas F Borchert, 2019